Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

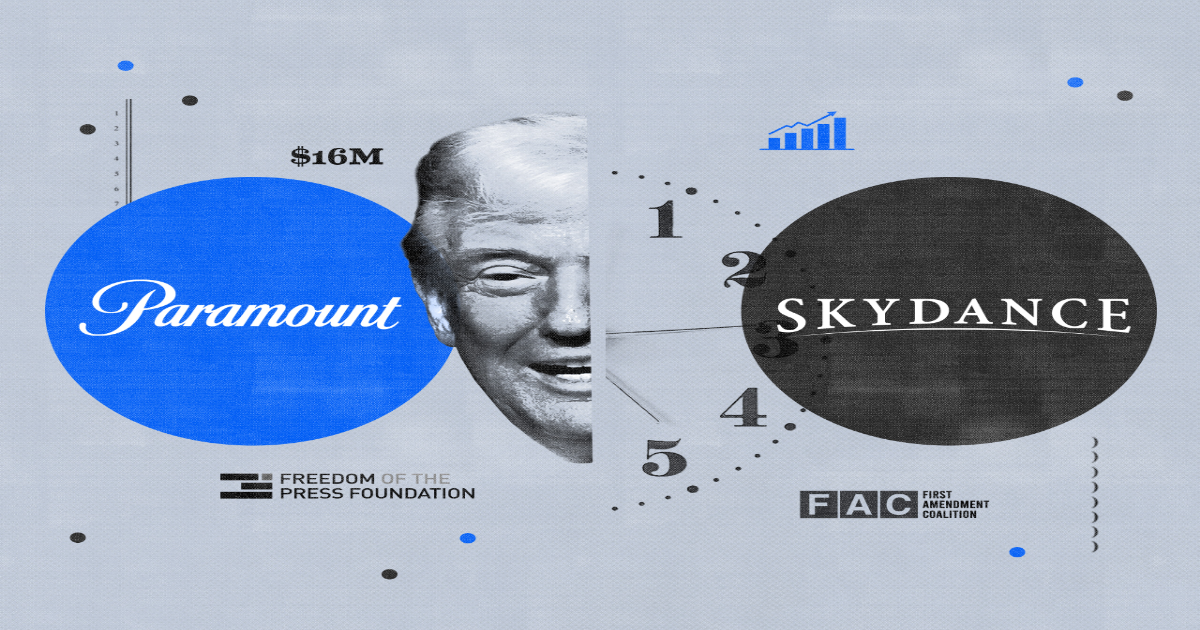

Early this month, as soon as the news broke of Paramount’s decision to pay President Donald Trump’s foundation sixteen million dollars to settle a lawsuit against CBS News, the Freedom of the Press Foundation moved to take legal action. The FPF, as it’s known, tracks and resists government infringement on the news media. It’s also a Paramount shareholder, prepared to push for those interests with corporate muscle. Trump’s case, and the response of Paramount’s board, immediately set off alarm bells, as the company was in the midst of pursuing an eight-billion-dollar merger with Skydance, a Hollywood studio, that required approval from the Federal Communications Commission. “They’re essentially making a handshake deal with Donald Trump,” Seth Stern, the FPF’s advocacy director, told me. He and the FPF’s legal team believed that such a deal could be a violation of federal bribery laws. And, he noted, Shari Redstone, Paramount’s controlling shareholder, stands to make two billion dollars from the merger. “I would think that, regardless of what Shari has to offer the rest of the board,” Stern said, “the prospect of potential prosecution for bribery would be something they would think quite hard about.”

Now it’s clear that Paramount’s board has decided the risk of prosecution is well worth a multibillion-dollar payday. On Thursday, the FCC signed off on the Skydance merger, clearing a path for its completion. “Americans no longer trust the legacy national news media to report fully, accurately, and fairly. It is time for a change,” Brendan Carr, the chairman of the FCC, announced, praising the deal for its commitment to “unbiased journalism” and assurances that “discriminatory DEI policies” will end. But when I spoke to Brenna Frey, a lawyer for the FPF, in the wake of the settlement announcement, she was incensed. “This is an affront to the shareholders of Paramount, but it’s also an affront to CBS’s reporters and to the First Amendment,” she said.

In Stern’s view, Paramount’s willingness to settle had been a calculated surrender. The premise of Trump’s lawsuit—that 60 Minutes’ editing of an interview with Kamala Harris last fall represented “fraudulent interference with an election”—was unlikely to hold up to legal scrutiny. “The lawsuit was laughable,” David Snyder, the executive director of the First Amendment Coalition, said. “What they were trying to attack here was CBS News’s choices about how they edited footage from an interview. That sort of editorial judgment is at the core of First Amendment protections, generally, but especially if it’s about public figures right in the middle of an election.”

But as a shareholder, the FPF had a right to do something about it. Back in June, the organization engaged Abbe David Lowell and Norm Eisen, both prominent litigators, as well as Frey, who had quit her previous firm, Skadden, over its offer of a hundred million dollars in pro bono work to Trump’s foundation. (In announcing her resignation, Frey had described that deal as a capitulation to “the Trump administration’s demands for fealty and protection money.”) Two days after the settlement was announced, the organization sent a letter to Paramount demanding that its board provide records relevant to the decision. Examining those records was a first step in putting together a shareholder derivative lawsuit, a mechanism of corporate law that allows the rank-and-file shareholders in a public company to recover damages caused by directors for making decisions that violate their fiduciary responsibilities. In their inspection request, the FPF’s lawyers suggested that Paramount’s board had breached those responsibilities by facilitating an illegal bribe.

That leaves the Paramount-Skydance deal, which is expected to wrap up soon and deliver an almost twofold premium on the current trading price of each Paramount share, subject to legal objection by members of its board. It’s not open-and-shut: Stern told me that building a case that the settlement actually damages the company’s bottom line would require the FPF to demonstrate that the board knowingly violated the law. But there is at least one precedent.

In 2023, Fox News agreed to pay Dominion Voting Systems 787.5 million dollars because the network had falsely claimed that Dominion software switched votes in the 2020 election from Trump to Joe Biden; afterward, some Fox shareholders sued Rupert Murdoch and the rest of the company’s board. That suit is still working its way through Delaware’s court system, where the FPF’s suit against Paramount would also be filed.

Scholars in corporate law are skeptical that either suit will be successful. “There’s been nothing like this before,” Ann Lipton, a law professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, said. “It is a very difficult claim to bring in the first place, but also I don’t think a Delaware court is going to want to step into the middle of this, politically.” Complicating matters further are some major changes to Delaware’s corporate legal code that went into effect this spring and limit the scope of the board records that shareholders are able to obtain.

Nevertheless, the FPF is displaying admirable creativity in putting legal pressure on Paramount. “If anybody has the resources to fight back against these kind of frivolous claims, these companies are it,” Synder said. Instead, they’ve chosen to make a “craven capitulation to a president willing to abuse his power.” As a result, Trump has been emboldened to assail press freedom like never before. Last week, after the Wall Street Journal reported that Trump contributed a lewd sketch and cryptic message to a book of birthday notes to Jeffrey Epstein, he followed up with a defamation lawsuit, writing on Truth Social, “President Trump has already beaten George Stephanopoulos/ABC, 60 Minutes/CBS, and others, and looks forward to suing and holding accountable the once great Wall Street Journal.” Can corporate law provide an unlikely means of protecting the independent press? The FPF seems to think that the stakes are high enough that it’s worth a try.

In legal circles, derivative suits are notoriously thorny. That’s because they contain a counterintuitive allegation: that a corporation’s board of directors has knowingly acted in a way that harms the financial prospects of the company each of them holds a large personal stake in. Another distinction of these suits is that the individual stockholders who file them are not seeking damages they’ll receive directly, but rather asking a court to award money from the directors to the company itself. Jennifer Arlen, a legal scholar at New York University, explains it like this: an individual stockholder (such as the FPF) sues the company to get the company to sue the board.

There have been successful suits of this sort filed against Blue Bell Creameries (over a 2015 listeria outbreak tied to its ice cream) and Boeing (in response to the disastrous debut of its 737 Max aircraft, which led to deadly crashes in 2018 and 2019). Blue Bell’s board of directors was forced to pay back sixty million dollars to the company; Boeing’s board returned 237.5 million dollars to the corporation, the largest-ever payout of its kind. Successful derivative suits like these must show that a board’s decision to intentionally ignore or skirt regulations led to a “mission critical” failure.

Such failures are obvious enough when they take the form of ice cream poisoning consumers or airplanes falling out of the sky, but what it looks like for a media company is more challenging to define. The legal system generally gives media companies wide latitude to operate under the First Amendment, so it takes a rare case like a successful defamation suit for a court to find that a network’s reporting may have led to a “mission critical” failure. Last year, a judge in Delaware did exactly that in denying Fox’s motion to dismiss the derivative suit it is facing. In the ruling, he sided with the plaintiff’s argument that Murdoch and the rest of the company’s board consciously broke the law by facilitating the defamation of Dominion.

The Fox case is still a long way from being resolved: in April, both sides began a discovery process meant to uncover the extent of the relationship between one of Fox’s directors, Jacques Nasser, and the Murdoch family. If the court finds that Nasser was not compromised by his relationship with Murdoch, the case will likely be dismissed; otherwise, the company will probably seek a settlement. “These cases don’t go to trial,” Arlen explained. That’s because damages ordered by a court aren’t covered by corporate liability insurance, while settlement payments are.

For the FPF, it may prove challenging to bring the same sort of case against Paramount that Fox News has now been fighting for two years. In part, this is because the FPF needs to establish clear documentation of wrongdoing. The plaintiffs in the Fox case made their complaint based on information that became public during the Dominion lawsuit. The FPF currently has much less information to go on. Some members of Paramount’s board were concerned that settling with Trump could lead to criminal bribery charges, as reported by the Wall Street Journal and New York Post—but the FPF will almost certainly need evidence of those deliberations. The only way to get that is through the inspection request the FPF submitted to Paramount shortly after the Trump settlement.

Unfortunately, the scope of what the organization will be able to access was limited by the recent changes to Delaware law. Whereas it was previously feasible to obtain communications between directors in certain circumstances, that now appears almost impossible. “You can still get board-meeting minutes, but that’s not going to be useful at all,” Christina Sautter, a law professor at Southern Methodist University, told me. It’s hardly the kind of material that’s liable to produce a smoking gun.

Timing is also a concern. The clock began ticking on the FPF’s ability to even bring a suit against Paramount the moment the FCC approved the merger—and once the two companies officially become one, the window for litigation will close. “They aren’t going to be stockholders of Paramount anymore, and that means they will not have the right to bring claims,” Lipton, the UC Boulder scholar, said. Though the FPF’s shares in Paramount will convert into shares of the combined Skydance-Paramount, decisions made by the predecessor firm’s board will have no bearing on the new entity. The only option, Lipton said, is to get an injunction to delay the merger—but it’s hard to imagine a judge granting it.

“I don’t think any Delaware court at any time would have wanted to walk into the politics of this, and then you put on top of it that you’re catching Delaware at this really particularly vulnerable moment,” Lipton said. She highlighted how the recent changes to the state’s corporate code were made as a conciliatory gesture toward companies like Tesla, Meta, and Dropbox that have threatened to reincorporate elsewhere.

All of this adds up to a formidable challenge for the FPF, to put it mildly. Its lawsuit against Paramount is an attempt to win a free-speech argument in a courtroom where the First Amendment is simply not relevant. It’s like trying to put a square peg in a round hole, Lipton said. “As other regulatory avenues fall away, people increasingly turn to corporate law to bear that weight. It often seems like the only system that works—but it wasn’t designed to work like this.”

When I asked Arlen if shareholder derivative suits represent a plausible path toward forcing media conglomerates to abide by basic editorial and journalistic standards, she was much more blunt in her assessment: “No.”

The Freedom of the Press Foundation is only able to consider a long-shot lawsuit in the first place because broadcast news networks are all owned by a handful of publicly traded conglomerates. CBS News is a minuscule component of Paramount’s overall portfolio; the same goes for ABC News, which is part of Disney. (Disney made a similar deal as Paramount late last year, when the company agreed to pay fifteen million dollars to Trump’s foundation, plus another million to Trump’s lawyer, to settle a lawsuit over the way ABC anchor George Stephanopoulos described Trump’s sexual assault of E. Jean Carroll.)

But smaller news outlets have refused to kowtow to Trump. The Des Moines Register is currently fighting a lawsuit Trump filed over an outlier poll the paper conducted in November. After six months of legal jockeying—during which the president’s lawyers tried to force the litigation into a state court rather than a federal one—the paper has remained resolute. Last month, Lark-Marie Antón, a Register spokesperson, said the paper “will continue to resist President Trump’s litigation gamesmanship and believes that regardless of the forum it will be successful in defending its rights under the First Amendment.”

Compare that statement with how George Cheeks, the co-CEO of Paramount, justified the settlement with Trump. In a call with shareholders, he said that their situation was no different from any other litigation that management might face, and that “a negotiation resolution” would allow them “to focus on their core objectives rather than being mired in uncertainty and distraction.”

Paramount evidently viewed Trump’s suit as a business dispute. “With a business dispute,” Snyder noted, a settlement “often makes sense, because business disputes are often about money, and really not much more than money.” Battling constitutional threats, unfortunately, loses money.

Corporate consolidation has clearly compromised the editorial operations of CBS and ABC, much to the dismay of the journalists who work at each network. At the same time, other TV outlets are in the process of regaining some independence. Much of Comcast’s cable portfolio, including MSNBC and CNBC, will be spun off into a new company called Versant by the end of 2025. Those networks generated around seven billion dollars in revenue last year, but they still represented only about 5 percent of Comcast’s overall business. Should MSNBC face an extortionate lawsuit from Trump in the future, a smaller, media-oriented company would be much more likely to follow the Des Moines Register’s example than that of Paramount.

Still, if the FPF ultimately sues, and if it is improbably successful in delaying or blocking Paramount’s merger with Skydance, the action will serve as a warning to indifferent executives of media companies that, as Stern puts it, “authoritarianism is bad for business.” At the very least, the FPF’s legal pressure is drawing attention to Paramount’s disregard for the journalists it employs. “People can’t trust a news outlet that is bribing the same officials it’s supposed to hold accountable,” Stern told me, citing the recent departure of 60 Minutes executive producer Bill Owens and the firing of CBS News head Wendy McMahon.

Adam Rose, a former CBS employee and a stockholder in the company (which also employed his father, the longtime Southern California radio host Hilly Rose), said that the settlement has done irreparable harm to the company. “One of the few things that really commands a true national audience is a 60 Minutes interview with a presidential candidate,” he told me. “Moving forward, do you think that this settlement will encourage the presidential candidates to actually come on? Will they trust that CBS isn’t going to capitulate to their political rival?”

In any other era, the well-resourced legal team at CBS News would have been empowered to demonstrate the frivolity of Trump’s lawsuit in court. Instead, at perhaps the most trying time for press freedom in American history, it has become clear that corporate ownership is a serious liability—and journalistic independence will require vigilant defense, sometimes through esoteric tactics.