Last week, Ted Sarandos, the co-CEO of Netflix, said the streamer is currently “saving Hollywood” by encouraging film-makers to focus on making films that delight their own audiences, rather than cinema operators. It appears the company is wooing the demographic that wants to see Tom Hardy shoot a young woman through the head with a harpoon.

Such is one of countless nasty incidents in Havoc, the latest film from Gareth Evans, which launched on Netflix on April 25. Evans is the 45-year-old director of the acclaimed martial arts diptych The Raid and the Sky Atlantic series Gangs of London, and was poached by the streamer back in 2021, who wanted to bring his brand of skull-splintering action to the service. For Evans’s admirers, the sheer imaginative nerve of his work is all part of the fun – I can’t recall ever previously seeing an attempted murder by tumble dryer, though Havoc ticks that one off within its opening five minutes.

On both big screens and small, graphic violence has entered a new golden age. In cinemas, the unexpected success of John Wick, starring Keanu Reeves, in 2014, prompted a new cycle of the sort of so-called ‘heroic bloodshed’ films – featuring elaborate kills, impossible odds and superhuman endurance – that last flourished in 1980s Hong Kong.

Charlize Theron had Atomic Blonde, Bob Odenkirk was Nobody and Dev Patel Monkey Man, Brad Pitt took the Bullet Train, while Reeves returned in three increasingly ornate Wick sequels, each pushing both its star and genre to new extremes.

Further up the budget scale, studios began producing blockbusters whose levels of cruelty and gore ruled out box-office-friendly 12A certificates. The two recent Mad Max titles, Fury Road and Furiosa, leant into their disreputable B-movie roots, while recent treatments of both Batman and the Joker had more in common with serial killer procedurals than comic-book smash-’em-ups.

When it comes to TV, there is Evans’s Gangs of London, the grisly superhero satire The Boys, the stately, brutal Shōgun, and South Korea’s macabre Squid Game, whose life-or-death Krypton Factor premise made it an unlikely playground favourite.

If this all strikes you as gratuitous, you’re far from alone. The recent anxiety over screen violence in broadsheet comment pages is shared by the public at large. When consulting on their certification system last year, The British Board of Film Classification found that UK viewers’ tolerance was lessening.

In a poll of around 11,000 members of the public, 35 per cent cited violence as a major area of concern: up 10 per cent from the last survey in 2019. Violence ranked beneath sexual violence and domestic abuse, depictions of suicide and, ahem, sex scenes, but outranked everything else, including drug misuse, dangerous behaviour, discrimination and racism. And of 51 films shown to various civilian panels around the country, it was felt that in 16 cases – almost a third – the original BBFC rating had been too lenient on grounds of violent content alone.

Genre was only sometimes a mitigating factor. Viewers were content that the grindhouse mayhem of The Suicide Squad was permissible at 15, but felt that Joker’s malice and sadism merited an 18 – as did the old-school gangster whackings of The Many Saints of Newark, the (also 15-rated) Sopranos prequel. As for the violent scenes panellists believed had been rated too severely: well, there weren’t any – in fact, there was broad support for the BBFC’s practice of upping historical ratings to match more squeamish modern tastes.

Such see-sawing can sound odd in the abstract, but on a case-by-case basis, the earlier rating is always the one that seems mad. It’s hard to believe, for instance, that in 1980, Luke Skywalker wailing in agony as his hand is lopped off in The Empire Strikes Back was a totally unobjectionable U. (It was changed to a PG in 2021.)

Even so, explicit screen violence has its fair share of ghastly and slobbering admirers, and I’m not ashamed to say I’m among them. For our kind, violence is not unlike smoking: an obviously unhealthy behaviour in real life on which a well-handled camera can confer an incredible beauty, glamour and existential charge – take the mortal desperation of Heat’s central shootout, the sinuous elegance of the Zhang Ziyi-Michelle Yeoh sword fight in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, or the absurdist farce of Oliver Hardy versus James Finlayson (plus the preposterous build-up) in Blockheads.

The present heyday of on-screen gore has been in the works for some time. Its roots lie in the visceral horror that seeped into cinemas after 9/11, as images of Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib prisons swilled through the news. The smirking postmodern slashers of the 1990s, such as Scream and the I Know What You Did Last Summer series, no longer seemed funny, and were quickly supplanted by the punitive nihilism of Hostel and Saw.

“Torture porn”, the stuff was derisively christened – at the very moment that the online world made limitless quantities of images in both of those categories suddenly available to the general public. The coinage recalled a line written in 2003 by Susan Sontag about war photography: “It seems that the appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked.”

Even so, it might seem unthinkable that such images would ever escape the horror ghetto and break out into cinema and TV at large. But sleeper agents – including Havoc’s Gareth Evans, who had become fascinated by martial arts while filming in Indonesia in the late Noughties – had laid the groundwork in advance.

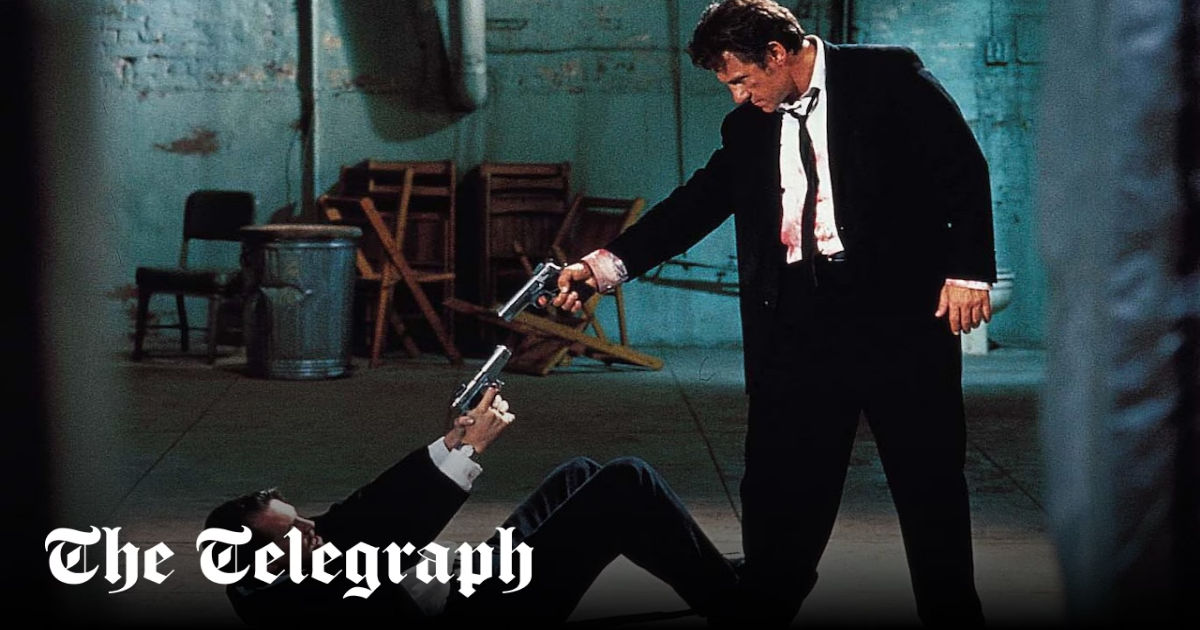

The generation of directors whose tastes had been shaped by Hong Kong action cinema of the 1970s and 80s began to come of age in the decade ahead. At the head of this sweaty vanguard was Quentin Tarantino, whose 1993 debut Reservoir Dogs borrowed elements of its plot, including its climactic Mexican standoff – that iconic three-way stalemate at gunpoint – from Ringo Lam’s 1987 heroic bloodshed classic City on Fire. (Tarantino would tirelessly champion Hong Kong cinema in the decades ahead, lending his promotional muscle to western releases while paying homage to the industry to hell and back in the Kill Bill films.)

Meanwhile, Lam’s contemporary John Woo relocated to Hollywood at the time of Reservoir Dogs’s release, seizing an opportune moment. A year after the release of 1992’s Hard Boiled, in which Chow Yun-fat memorably guns down an army of gangsters in an exploding hospital while carrying a newborn baby, Woo had already worked with Jean-Claude Van Damme in Hard Target; next came partnerships with Nicolas Cage (Face/Off), John Travolta (Face/Off too, plus Broken Arrow), and Tom Cruise (Mission: Impossible 2), all of which splattered the heroic bloodshed style across blockbuster canvases.

The violence in these films left western audiences stunned for two reasons. First, it was graceful: the kung-fu and wuxia films responsible for Hong Kong cinema’s own golden age, and on which directors like Woo had learned their craft, were full of extraordinary physical feats. Second, it was visceral, playing out on a personal scale, in medium shots and close-ups: every mission was a melodrama, rather than just muscle-bound gunmen running amuck.

And domestic censorship in Hong Kong was notably lax. The government body responsible was far more concerned about cutting political material that might provoke China than sparing the squirms of more delicate viewers.

At the apex of this cultural exchange sat two foundational millennial franchises: The Matrix and Charlie’s Angels, whose respective fight choreographers, the brothers Yuen Woo-ping and Cheung-yan, were both esteemed Hong Kong veterans. The mainstream success of those films sparked a new thirst in the west for the hard stuff, which newly flourishing international series such as Ong-Bak and Ip Man were only too happy to meet.

As was Keanu Reeves. Though his star had waned in the wake of the awful Matrix sequels, he used the resulting professional lull to both direct and star in the hidden gem of his career: an out-and-out old-school martial arts movie, 2013’s Man of Tai Chi. The first John Wick, released the following year, hadn’t originally been written in the same tradition: it began life as a ‘geriaction’ thriller called Scorn, designed for an actor in his 60s.

But Reeves – a youthful 49 at the time of casting – saw its heroic bloodshed potential, lobbied for a title change, and helped enlist directors Chad Stahelski and David Leitch, formerly of the Matrix stunt team. Hong Kong-style violence was ready for its Hollywood comeback – this time with a Hong Kong-style appetite for savagery and shock.

For directors like Evans, a credible path to the mainstream had finally been hewn. (Actually, better make that beaten.) His sequel to The Raid had surfaced just months before Wickmania kicked in, and in this new no-holds-barred climate, it wasn’t long before Sky tapped him up to direct Gangs of London, a generously-budgeted UK production. As for Stahelski and Leitch, both have since remained endlessly busy, hammering out three further Wicks, a Deadpool sequel, Hobbs & Shaw and more between them.

That Havoc exists at all is thanks to this decade-long shift and the audience it created. Once you’ve watched The Rock massacre his foes with a ceremonial axe in a Fast & Furious spin-off – and note that a further shot of him biting out one of their eyeballs had to be cut – Tom Hardy tearing his way through an army of Triads is a logical next step. So if you’re browsing for something new to watch tonight and his bristly visage pops up, don’t say you weren’t warned.

Havoc is on Netflix now